I aspire to be the steady trajectory of a creode yet my Homo Sapien self settles into a homeostasis of disinterested listlessness. What will I “do?” Who should I “be?”

Two weeks past, I walked the botanical gardens with three close friends and two kids. Kids need to eat, so we ate lunch in the atrium. The table grew a crop of floribund crumbs from hot dog buns and overly dyed rainbow cake. As we were about to depart, two women at the next table called me over with the universal four-fingered “come here” gesture, the caress to the underbelly of the invisible sea lion that was the atmosphere. Both were bright of eye and grey of hair; two sisters who were retired teachers with nearly 90 years of experience between them.

Without embarrassment, one of the sister-teachers said to me, “We’ve been eavesdropping. We listened to you with the kids, and being longtime teachers, we just KNOW,” she emphasized the word “know” into a block of concrete - an undeniable knowing, “that you must be a teacher.” They waited for me to confirm, on the edge of seat and delight, until I replied that I wasn’t a teacher. They were as shocked as I was honored. We chatted for a bit, and I shared the sparse memories from 2010 when I was a mentor for a writing program modeled after the 826 Valencia project

The closest I’d ever come to teaching.

It was that experience that made me realize I could never be a teacher because of the attachment I had to one particular mentee, a young man named Gerardo.

I’ve been thinking about this since. . .so much so that I searched the word “Gerardo” in my email, as I was certain I must have emailed about the experience at some point. No fewer than 25 results appeared. I wrote about Gerardo to fellow mentors, to my best girlfriend in Seattle, to my family. I even told Elisabeth that if I didn’t have plans to be in Seattle with her for Thanksgiving that year, I’d surely bring Gerardo to my family’s dinner, as he had nowhere to go.

Gerardo’s neck was bound by a blinged-out cross, and the white-heads of puberty adsorbed his forehead like cold dew on hot glass. He was also slow to open. But we are all frozen wood frogs at first until a caress along the dissection line coaxes open our blue-filled limbs.

I favored Gerardo. Wanting to cradle him. Wanting to give him what the world took away. I’d forgotten tho, until reading the emails about him, that he grew an attachment to me as well; preferring to work with me over other mentors. Maybe the word isn’t attachment so much as trust. Could I sustain that trust with more than one student at a time? Is it even ethical?

In the feedback, Gerardo wrote about his initial wariness of the project but how my every morning smile put him at ease. I used to keep that note on my wall until I stashed it away in my literal picnic basket full of memorabilia because it made me feel more like a hack than a human. But it wasn’t about me; never was. It was about Gerardo and the other students who heroically eviscerated themselves, turning graphic to graphite and compiling their stories into a book titled “In My Shoes: Teen Reflections on Hope & the Future.”

Each mentor was asked to write a bio of the student they worked with, and this is what I wrote about Gerardo:

Gerardo gives fully of himself to the reader. As he offers up the truths of his mind and his heart, he invites the reader to understand their own truths. Gerardo writes with his senses, giving the reader the entirety of his experience through his nose, his mouth, his eyes, and his ears. His self-awareness, observance of his surroundings, and knowledge of right and wrong will continue to build him into a great man.

The reference to “right and wrong” makes me relfex with the pain of chewing tin foil.

What else I’d forgotten that I re-remembered by reading my own email correspondence with others:

I forgot how astutely Gerardo wrote about his mom abstaining from meth for 30 days: “Her face starting to come back into shape and her hugs actually had meaning again.” Addiction becomes our child; we feed and nourish it, while our children become our caregivers.

I forgot how I used to rigidly follow the grammatical rule for prepositions and endings. I wouldn’t say I’ve learned a lot from my father, but one lesson he consistently and hilariously imparted to me was to never end a sentence with a preposition. He’d reinforce the rule by joking, “If you won’t remove the proposition, then just add the word asshole to the end of the sentence.”

I’d forgotten it was a friend and author, Timothy Shaffert, who set me free from the bondage of my entangled relationship with the placement of prepositions. The freebase morphemes of “of” and “at” and “on,” all with their open opening letters, begging for two fingers or one tongue.

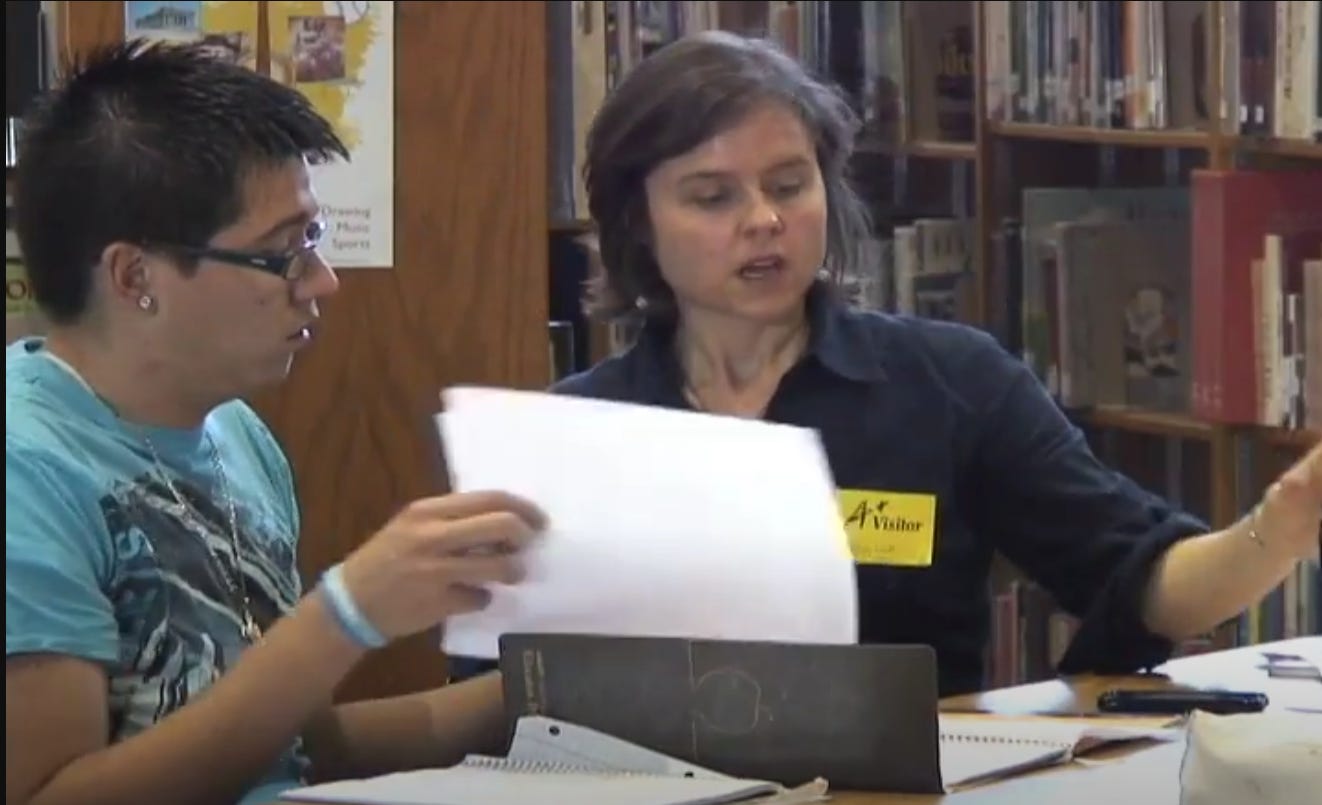

I forgot that a video exists from that time. Gerardo and I are first seen at the 5-second mark. Faces from 13 years ago of kids not much older than the time that has passed, and faces of friends and acquaintances I no longer see.

I forgot I used to wear jewelry on the daily.

I forgot about the foxy fellow mentor, 18 years older than me, who I skirted the auricle edge of an affair with.

But the most gutting remembering was unearthing the forgotten feeling of unmitigated purpose I had every morning when I walked into the library at Omaha South High School. It wasn’t the being needed that I now miss, it was the having a reason to exist.

iirc one of your close friends described you as a gardener, and i totally agree 💗 you see the thing in people which we wish to see in ourselves and you coax it out of us. call it teacher, mentor, gardener, what have you... whatever the label, it’s a joy to witness and be close to 🥲

I get this. Completely. Especially the element of purpose. Thank you for sharing your words and memories in a way that always triggers something in me as a reader.